The concept of induction (the kind of reasoning that leads us to draw general conclusions or make predictions concerning unobserved cases based on cases we have observed) has a long tradition in philosophy, which is worth revisiting.

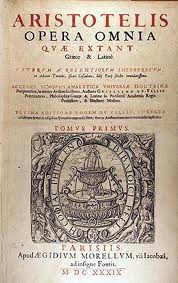

Aristotle was the first to concern himself systematically with induction and he gave it a foundation based on the whole of his metaphysics, that is, what he thought concerning the nature of reality and knowledge. For Aristotle, scientific knowledge was essentially a system of classification. In a world of beings which organise themselves and rank themselves according to unchangeable forms or essences, a scientific statement confirms that an individual belongs to a certain species or that a certain species belongs to a genus. The individual is the specific case, the particular; stating that he belongs to a species defines his essence and shows what is universal in him.

According to Aristotle, the universal elements, the essences, exist in things, in particulars. Induction (in-ducere, to lead inward) consists precisely in this recognition of the concept (the universal) within the sensible (the particular). As we observe the behaviour of a phenomenon in various particular cases and recognize a regular pattern, we are naturally led to infer that this regular behaviour is a sign of the essence of the phenomenon and to forecast that the same behaviour will be shown in cases which will be observed in the future. This is basically the way in which Aristotle understands and justifies induction.

After 2000 years of almost complete dominance, Aristotle’s metaphysical ideas were challenged by modern philosophy. Hume, in particular, rejected Aristotelian essentialism, thus undermining the basis of induction. The link between particular cases and general law no longer depends on the presence of the universal within the thing and comes to be seen as simply the result of subjective expectation based on habit. This does not imply that Hume rejects or undervalues induction as a resource to be used in daily life or in empirical science: he simply removes the claim that knowledge obtained through it has an absolute, unquestionable metaphysical truth.

Hume’s criticism of Aristotle’s theory of induction did not prevent logical empiricism, the dominant concept in the philosophy of science until the 1950s, from defending an inductivist view of scientific method. It was felt that the general laws of empirical sciences were obtained through induction from the observation of specific cases, thus consisting in a simple summary or ‘condensation’ of concrete experience. As well as being acquired by induction, for the logical empiricists general laws could also be proved inductively. The greater the number of positive examples (specific cases conforming to the law) that could be observed, the greater would be the level of confirmation of the law or hypothesis. Actually, laws were only hypotheses with a sufficiently high degree of confirmation. The idea of the degree of confirmation led to attempts to apply calculations of probability to this discussion, but without any great success.

The discrediting of the inductive conception of scientific method was to a great extent the work of Popper. Proper claimed to have solved the problem of induction in a new and radical way: simply showing that the problem of induction does not exist in empirical science for the good reason that empirical science is not inductive. Scientific hypotheses are not obtained by inductive generalisation nor are they proved by the repetition of positive cases. Science moves forward by conjecture (bold generalisations with no logical support from experience) and refutations. What strengthens our hypotheses is their resistance to the clever and honest attempts to refute them to which they are subjected and that they manage to survive. Popper calls this process corroboration.